Market Overview and Desired Specs

This article contains an overview of similar solutions that already exist and how my project compares to them. For this classification, I would like to define targeted specifications that my loom should be able to achieve (testable, quantifiable, verifiable).

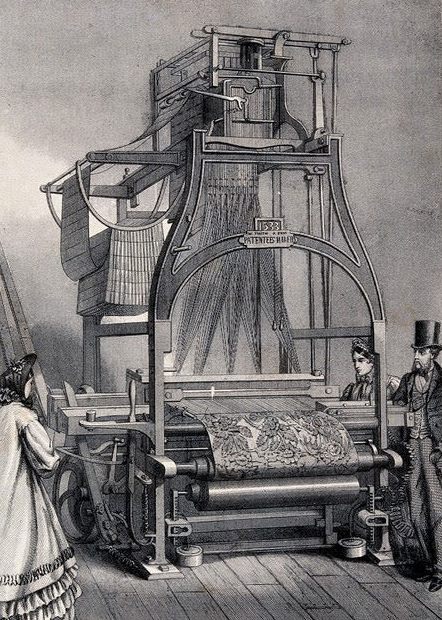

Weaving is considered to be the first technique for the production of fabrics and therefore belongs to the oldest artisan crafts of humankind. The history of weaving goes far beyond our historical records and findings. The fabric production tools have also become increasingly advanced over the course of thousands of years. The automated weaving loom was one of the significant technological breakthroughs and is considered to be a symbol of the industrial revolution. It marked the transition from the age of manual craftsmanship to industrial mass production. Through the use of punch cards, the Jacquard loom is also considered to be the first programmable device and inspiration for the first computers. Modern industrial looms are almost completely automated and reach unimaginable unattainable speeds.

This project aims to revisit the transition from manual labour to large industrial machines, using modern technological capabilities to recapture, democratize, and make the production method available for everyone.

The table provides an overview of modern computerized Jacquard looms, aside from large-scale industrial tools. The looms vary significantly in their commercial availability, type (handloom/serial), technical details, price, size and form factor, the density of warp threads and setting speed.

| ID | Name | Manufacturer | Website | Type | Technical |

Commercial Available / Open Source Hardware |

Estimated Price Without Shipping and Taxes | Form Factor | Warp Density | setting speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC2 | Digital Weaving Norway / Tronrud Engineering | Link | Handloom, parallel | Heddle wires are lifted directly by a vacuum pump and custom electric valves | Commercial available |

32000€ base loom without hooks modules costs for the vacuum pump are not included 3450€ 220-hook module (15,68€ per hook) |

standalone width: 122 cm - 198 cm length: 171 cm height: 155 cm |

modules with 220 hooks can be stacked resulting in max. 47.79 ends per cm or 180 epi |

instant <1s |

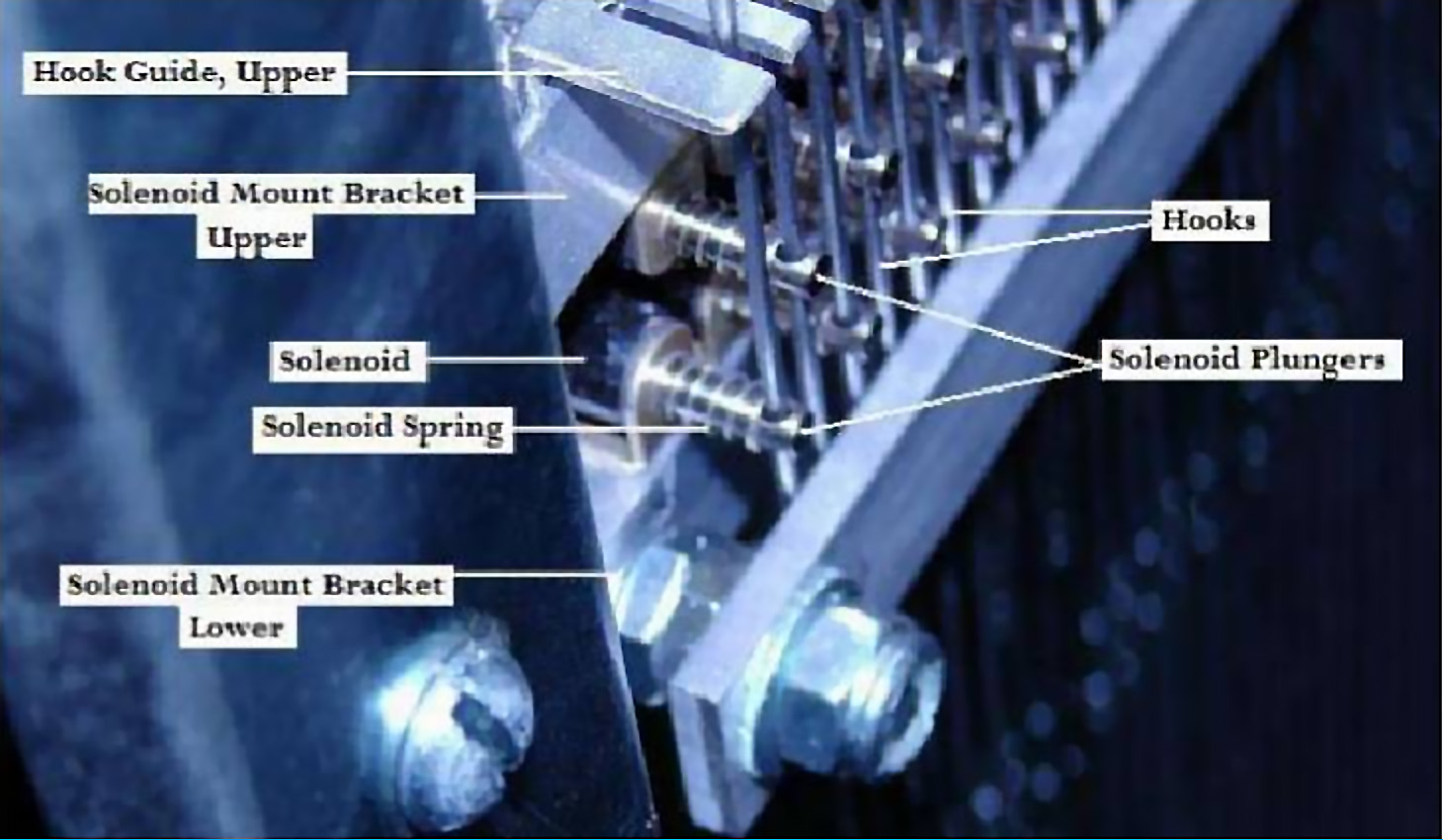

| 2 | Jac3g | AVL | Link | Handloom, Parallel | A solenoid on each heddle wire engages or disengages it with a lifter bar | Commercial available |

16786.47€ base loom without hook modules 4484.8€ 120-hook module (37,37€ per hook) |

standalone width: 114 cm - 218 cm length: 167 cm height: 214 cm |

modules with 120 hooks can be stacked A special mechanism increases the epi up to a factor of 10 by making the tissue narrower. In the widest form that results in max. 11 ends per cm or 28 epi. In the smallest form that results in max. 110 ends per cm or 280 epi. |

instant <1s |

| 3 | OSLoom |

Benitez, Clark, Yanc, Vogl, Benett, Shimomura |

Link | Handloom, Parallel | Muscle Wire tied to each heddle wire engages or disengages it with a lifter bar |

Successfull Kickstarter. Used to become OSH but plans were never released. Project not continued. |

Build cost estimated >1000€ |

standalone, estimated width: 80 cm length: 160 cm height: 200 cm |

hooks: 66 estimated width: 50 cm results in 1.32 ends per cm or 3.35 epi |

estimated 2s |

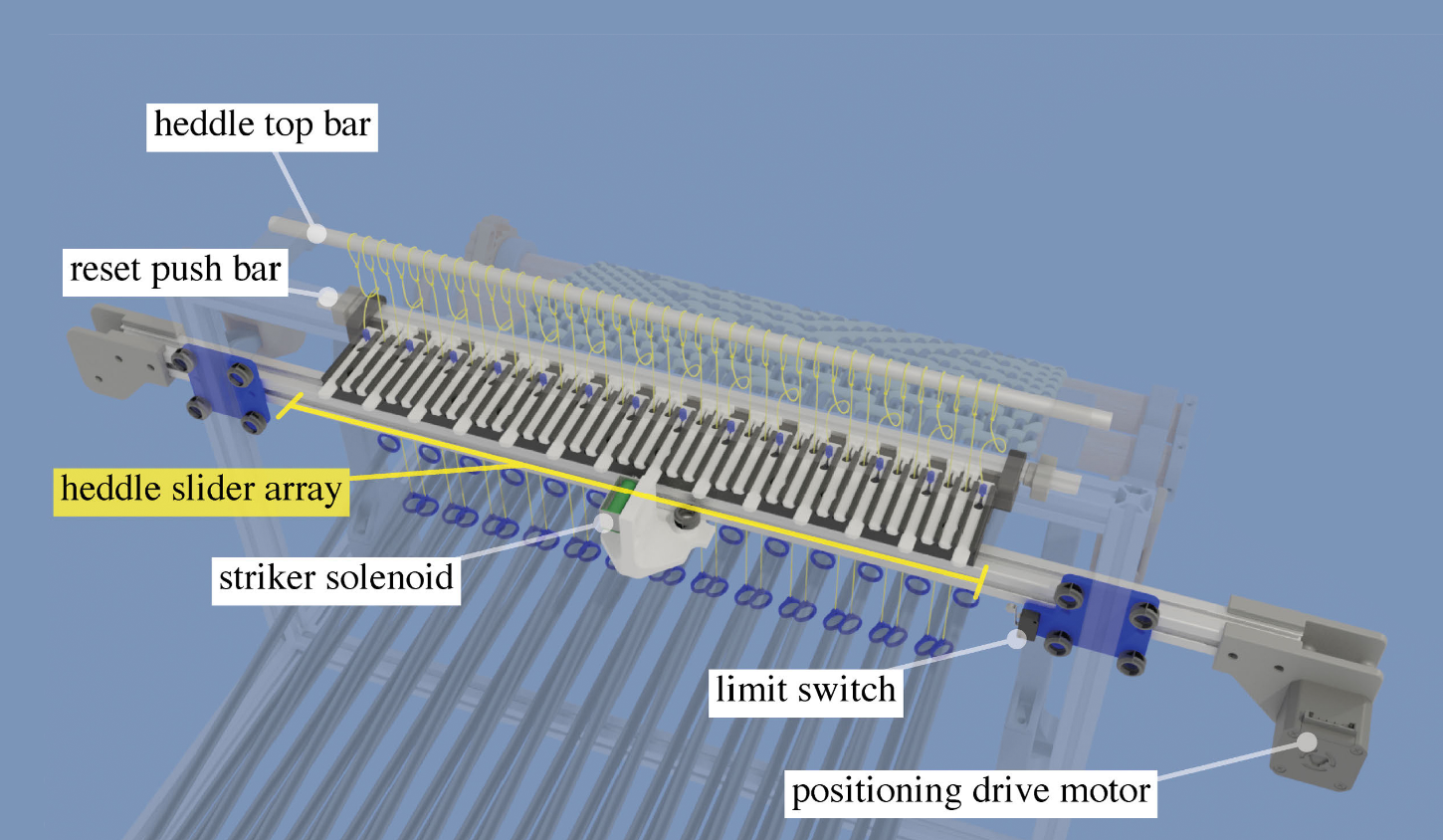

| 4 | Low-Cost Jacquard Loom | Albaugh, McCann, Yao, Hudson | Link | Handloom, Serial | A carriage with a solenoid pushing each bistable mechanisms attached to each heddle wire to to engages or disengages it with a lifter bar | Not commercial available, CAD files and code available, license unclear | Build costs under 200€ | Tabletop |

hooks: 42 estimated width: 42 cm results in 1 ends per cm or 2.54 epi |

depending on the pattern setting speed in the demonstration video video 6.5s resulting in 6.46 hooks per second |

| 5 | FabLoom 2.0 | Edward Muñoz | Link | Handloom, Parallel | Hobby Servo Motors attached to each heddle directly | Not commercial available, detailed build log, OSH? license unclear | Build cost estimated 200€ | Tabletop |

hooks: 80 width: 20 cm results in 4 ends per cm or 10.16 epi |

instant <1s |

| 6 | Doti | Pamela Liou | Link | Handloom, Parallel | small linear actuators lift each heddle directly | Not commercial available, Claims to be OSH, files and documentation never released, license unclear | Build cost estimated 250€ | Tabletop |

hooks: 16 estimated width: 35 results in 0.46 ends per cm or 1.16 epi |

instant <1s |

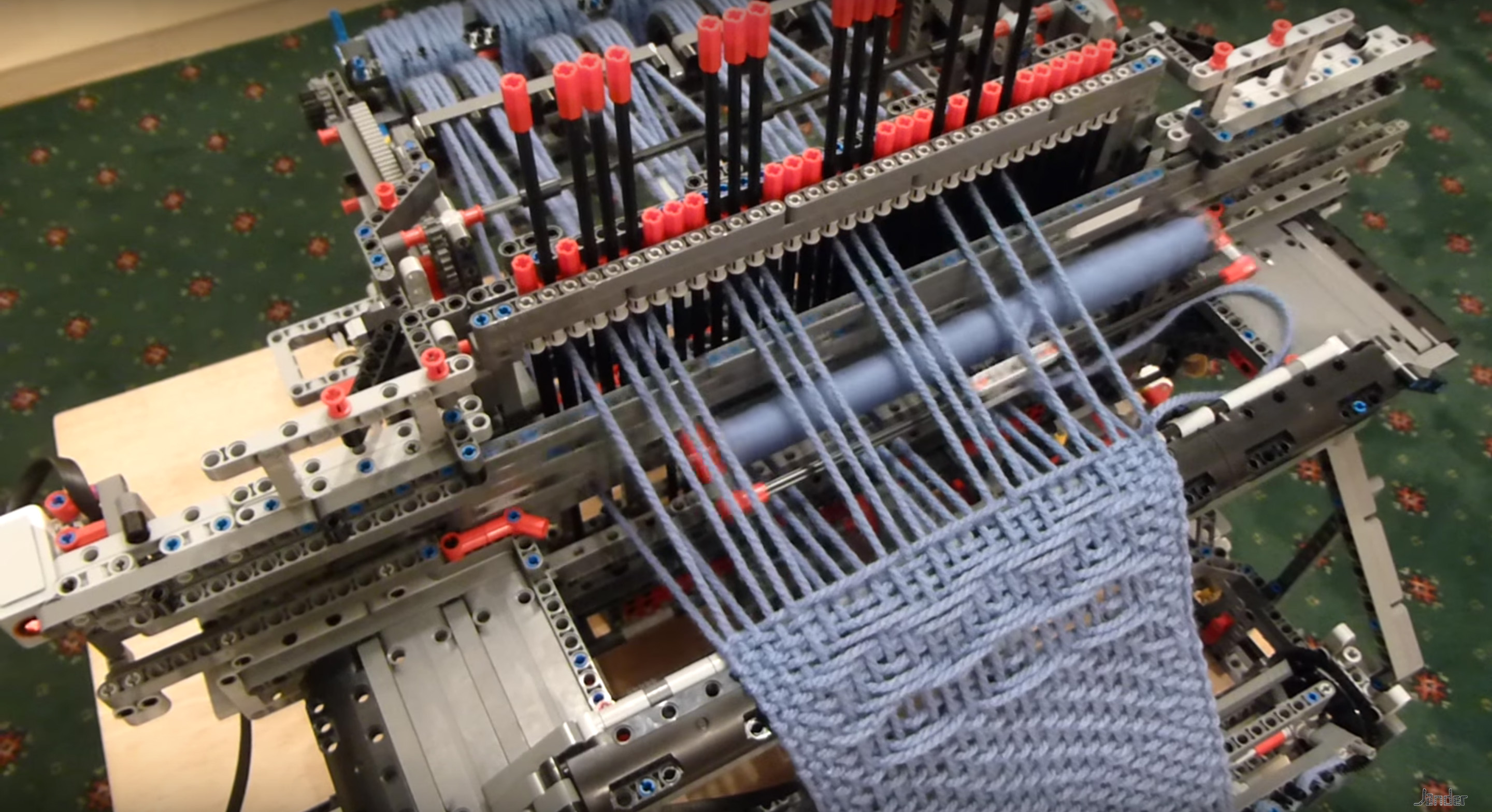

| 7 | Weav3r | Jerry Nicholls | Link | Automatic Loom, Serial | A carriage with a motor moving pins to engage or disengage the heddle wires with a lifter bar | Not commercial available, Nicholls wanted to release building instructions but never released | ? | Tabletop |

hooks: 32 estimated tissue width: 20 cm results in 1.6 ends per cm or 4.1 epi |

setting speed in the demonstration video 18s resulting in 1.78 hooks per second |

| 8 | WeaveMe | Schaefer | Link | Handloom, Serial | A long rod with a rotating key shaft moves eccentric disks to engage or disengage the heddle wire with a lifter bar | Not commercial available, OSH (MIT license) | Estimated build cost 300€ |

Tabletop Machine size twice the width of the fabric because of the moving rod |

hooks: 60 estimated tissue width 30 cm results in 2 ends per cm or 5.08 epi |

setting speed in the demonstration video about 1 hook per second |

| 9 | Jacques | Norman Heck | Link | Handloom, Serial | A carriage moving hooks with a pressurized air nozzle to engage or disengage heddle wires with a lifter bar | Not commercial available, OSH (license to be defined) | Planed build cost <500€ for the loom with one module | Tabletop |

with one module: hooks: 100 (parametric) estimated tissue width: 40 (parametric) results in 2.5 ends per cm or 6.35 epi (fixed) two modules can be stacked to double the epi modules should be stackable to increase the epi |

at least 10 hooks per second, preferably 20-30 hooks per second |

The looms listed in the table can be divided into two groups: Commercially available products and personal or scientific projects. The commercial looms mainly address advanced home users and small production environments. In comparison, the two commercial products can be considered real production tools, while the others are in a proof-of-concept state and unsuitable for producing functional textiles. This is especially evident in the density of the warp threads but also in the setting speed, rigidity and reliability of the machines. With non-commercial looms, only very coarse fabrics can be produced, while the other commercial looms can produce very dense silk fabrics. However, this immense difference also reflects in the price tag. The material costs of the non-commercial projects are located in the low three-digit price range. The commercially available looms are priced far above that and will cost about 50000€ (depending on the configuration). Besides the base price of these devices, the price per warp thread is also interesting - it shows how expensive the mechanism for selecting the warp threads really is.

My loom will be published under an open-source hardware license. It is still unclear whether it will reach market maturity and will be distributed commercially, as an assembly kit, for example. The material costs of my loom are higher than those of other non-commercial projects, but it should still be affordable and far lower in price than the commercial models. The higher price is justified by the fact that my loom can achieve more warp threads and, therefore, a greater fabric density; it will also be reliable and solid built.

The looms can be further differentiated into two groups by looking at the warp selection mechanism. The large-scale industrial products control the warp threads via thousands of actuators moving simultaneously. This makes it possible to achieve an extremely high operating speed. The large quantity of actuators leads to the high price of the products. Since an actuator is attached to each warp thread, the power requirement also increases with each additional warp thread. The two commercial products listed in the table (1 and 2) fall into this category. Most non-commercial Jacquard looms also use similar parallel control mechanisms. The reason why the estimated construction price is nevertheless relatively low can be explained by the small reduced number of actuators (width and warp density). In the table, I have only listed Osloom (3), the much smaller FabLoom 2.0 (5) and Doti (6) as examples to avoid redundancies. A few more non-commercial Jacquard looms can be found online, but they are very similar in construction and not as technically advanced.

In contrast, the serial selection method only uses a few actuators to select the warp threads one after the other. The listed looms (4, 7, 8) use two actuators: one actuator controls a carriage in the direction of the weft, while the other actuator selects each warp thread as the carriage passes by. This method is much slower in operating speed and depends on the mechanism, the warp threads’ density and the fabric’s width. By eliminating thousands of actuators, this mechanism is comparatively inexpensive to implement. The power consumption of these serial mechanisms is also much lower due to the reduced number of actuators. It remains the same no matter how broad or dense the fabric is. The maximum density of the warp threads is also limited: one cannot select objects that are arbitrarily close together. One must work with several stacked selection carriage modules to achieve a higher density. With the simultaneously controlled mechanisms, you have quite similar problems. Due to the size of the actuators, it is necessary to stack several modules behind each other to increase the warp density at a certain point.

My loom should also fit into this relatively new category of serial Jacquard looms. When I started thinking about low-cost Jacquard weaving, only one loom was available that used a serial selection mechanism. I immediately recognized the potential of this idea and thought about how one could further improve the setting speed and make a fully functional production tool with this approach. In the meantime, two more looms of this type were developed and have proven that it is possible to build a functional loom with this mechanism. However, all three projects have failed to produce what I consider acceptable speed, ease of use, decent fabric density and reliability. I’m confident that the serial selection mechanism can perform better; I’d like to increase my machine’s setting speed and fabric density drastically. I would like to achieve a warp density of 2.5 ends per centimetre (4mm hook spacing) with one module. In addition, I would like to think ahead and implement the possibility of consecutively stacking multiple selection modules to further increase the density of the fabric in the future.

Weav3r (7) is the only automatic loom on the list; it can weave completely independently. All other looms belong in the category of (computer-controlled) hand looms. While the shed is formed automatically on these, a weaver must still insert the weft thread by hand and control the tension and weft density. This is not necessarily a disadvantage: the two commercially available looms (1, 2) also belong to the group of handlooms. A handloom offers more design possibilities and room for improvisation. It allows the work with materials that cannot be processed in an automated machine otherwise. However, with a serial control of the warp threads, it would make sense to insert the weft automatically. The best example is Schaefer’s loom: He has by far the slowest actuation speed and relies on inserting the weft thread by hand. In his video, he doesn’t show how long it really takes for the mechanism to form the shed. But you can see in the video that it’s apparently very slow. With the required presence of an operator and such a long waiting time, this loom is certainly not suitable for actual production. If the loom was completely automatic, a fabric could be produced unattended over a longer timespan despite the slow operating speed. In the target group of home users, the operating speed is not significantly important when the loom can be left unattended.

Because of the advantages mentioned above, I also want to develop a handloom. Another reason is that I don’t want to work on another big tool component besides the warp selection mechanism at this stage of development. I can envision that the modular design will allow the weft to work automated at a later stage. Right now, developing a weft insertion method (using shuttles, projectiles, grippers, magnetic timing belts or nozzles) exceeds my time resources. Even though many solutions have been developed, the mechanism and its fine-tuning are, in fact, complicated: the thread tension and monitoring by a runout sensor is not an easy task. For multicoloured fabric, a colour changer is additionally necessary.

Due to my specification as a handloom, it is crucial to minimize the setting speed to prevent restricting the user and causing long delays. One goal is to optimize the warp thread selection mechanism for speed and reliability. It should work much faster than the other serial machines in the table. In my spreadsheet, I set the target of being able to select 10 hooks per second, although I would prefer to achieve the selection of 20 to 30 hooks per second. I currently expect to implement 100 hooks per module and, therefore, a maximum setting speed of 10 seconds. This is close to the limit of what is tolerable for the user and should be optimized in the future. One solution for reducing the users waiting time is an asynchronous preselection of the hooks. While the user is condensing the weft thread with the reed, the mechanism could already preselect the next row. This could make the mechanism feel instantaneous and responsive to the user’s input.

Edit